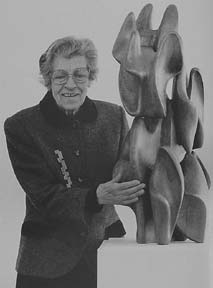

1916 – 2017

Born in 1916 in Ain el Mreisseh, Beirut, Lebanon, Choucair came from a family of doctors, lawyers, engineers and historians. Her father, Salim Rawda (1872-1917) was an expatriate in Australia trading herbs and writing manuscripts on their medicinal values. When he returned to Lebanon in 1910, he met and married Choucair’s mother, Zalfa Amin Najjar (1891-1995), a Brummana High School student who was fond of reciting poetry. They had three children: Anis Rawda (1911-1988) was a businessman and a member of the Beirut municipality; Anissa Rawda Najjar (1913-2016) was a social activist, who was married to the late Fouad Najjar; and the youngest, Choucair, became one of the most prominent figures of Lebanese modernism. When Choucair’s father was in Damascus as a conscript in the Ottoman army, he contracted typhoid and died in 1917. Widowed early on, Choucair’s mother had to raise three children on her own and under difficult circumstances. Choucair found inspiration within her mother; aside from being well-educated, a skilled orator and a poet, Najjar had also belonged to various women’s associations and was awarded a medallion from Brummana High School upon turning 100.

Art was a part of Choucair’s life from the very beginning, and she believed that, for her, “art is innate.” She produced numerous hand-crafted objects at a very young age. When she was enrolled into the Ahlia School in 1924, she designed a multitude of school posters and was known for producing caricatures of her teachers, some of which were published in the school’s newspaper. She claimed to have been far more advanced than her actual art teachers and would roam the classroom to assist those who needed help with their art. In an interview with Nelda LaTeef, Choucair recounted her mischievous behavior in the classroom stating: “For my sociability, I spent most of my time out in the corridor!” After high school, Choucair attended the American Junior College for Women (currently the Lebanese American University) in 1934 and graduated with a degree in natural sciences in 1936. In 1942, Choucair took art lessons with Omar Onsi for three months, and that was ultimately the only formal art training she had received by that point in time, having learned most of everything else on her own.

Choucair’s travels were also what ultimately ended up influencing her artistic production. In 1943, during World War II, the artist went to Egypt looking to find some art, but all the museums were closed as a result of the turbulent climate of the time. So, Choucair instead decided to walk around the streets of Cairo and visit the mosques she encountered, and the experience inevitably had an impact on her. “It was thrilling! I thought this was real art! It endures,” she had exclaimed in her interview with LaTeef. In a world with a fast-growing technological industry, Choucair sought refuge in Islamic Art and found it to be a timeless form of art through which she could simultaneously develop her love of art and architecture. “It is my second love,” she said to LaTeef of architecture, “I started out as a painter and then moved to sculpture.” The combination of architectural and Islamic elements became central to Choucair’s artistic production, and Chris Dercon, former director of Tate Modern, emphasizes the fact that the artist chose to call into question the one-sided, Western view people often have when looking at Islamic Art. Instead, she explores principles of Islamic design and Arabic poetry within a modernist, non-objective artistic lens. Her sculptures are precise and geometric, and she tells LaTeef that her geometry is based on the proportions of the circle: “The essence of Arab art is the point – from the point everything derives.”

After her seven-month stay in Cairo, Choucair returns to Lebanon and begins working at the American University of Beirut’s (AUB) library in 1945 while simultaneously enrolling in some philosophy and history courses. It is there that she meets Moustapha Farroukh, president of AUB’s Art Club at that time, in 1946 and audits his art class every week. Farroukh also decided to publish one of Choucair’s drawings in the club’s only issue of Art Gazette. In 1947, Choucair exhibited some of her geometrical gouache drawings at the Arab Cultural Gallery in 1947, and the exhibition is considered to have been the Arab World’s first abstract painting exhibition. After that, Choucair decided to leave Lebanon again in 1948 to head to Paris with her brother-in-law, Fouad, who had to travel there for business. Initially, she did not know much about the global art scene beyond Post-impressionism, which is why she wanted to go to Paris and expose herself to everything that she had found in the news over the years. It is there that she encountered abstract art for the first time, having roamed the Parisian streets in search of art galleries and museums to visit while Fouad attended to his business affairs during the day. When it was time for them to head back to Lebanon, she decided to remain in Paris and enrolled herself into the École Nationale des Beaux Arts. During her three-and-a-half-year stay in Paris, Choucair observed and contributed to the thriving art scene of the region, joining Fernand Léger’s studio in 1949. However, she ended up leaving his studio three months later upon realizing that its concepts and methods did not coincide with her goals in artistic production.

In 1950, she was one of the first Arab artists to participate in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in Paris. Before returning to Lebanon, she had her first exhibition in Paris in 1951 at the Colette Allendy gallery, and the solo show included works she had originally displayed in Beirut, in addition to paintings she produced during her time in Paris. The exhibition was far more successful than the one in Beirut, and critics from the Art and Art d’Aujourd’hui magazines enthusiastically reviewed her work. The Art d’Aujourd’hui critic made special mention of Choucair’s work, comparing her bold forms to those of a “stonecutter” and writing that “the walls of Galerie Allendy are about to burst with the force of the paintings hanging there this week.”

In 1959 she began to concentrate on sculpture, which became her main preoccupation in 1962. In 1963, she was awarded the National Council of Tourism Prize for the execution of a stone sculpture for a public site in Beirut. In 1974, the Lebanese Artists Association sponsored an honorary retrospective exhibition of her work at the National Council of Tourism in Beirut. In 1985, she won an appreciation prize from the General Union of Arab Painters. In 1988, she was awarded a medal by the Lebanese government. A retrospective exhibition organized by Saleh Barakat was presented at the Beirut Exhibition Center in 2011.

In 2013 the Tate Modern held the first international retrospective of Choucair’s work.

Choucair’s work has been considered as one of the best examples of the spirit of abstraction characteristic of Arabic visual art, completely disconnected from the observation of nature and inspired by Arabic geometric art.

Choucair received a prestigious honorary doctorate from the American University of Beirut (May 2014).

Her artwork “Poem” is on loan to Louvre Abu Dhabi.

Choucair turned 100 in June 2016. In 1953, she married journalist Youssef Choucair, and they conceived one daughter together, Hala, who also became an artist. Her older sister, women’s rights leader Anissa Rawda Najjar, lived for almost 103 years, but her daughter had been killed during the war.

Choucair died on January 26, 2017, in Beirut.

Source: Wikipedia

Saloua Rouda Choucair Foundation